The Rise of the Narrative

“So Scheherazade began.” Arabian Nights

History will decide how and why the Taliban were able to recapture Afghanistan without effective opposition. For now, we rightly concentrate on the plight of those trying to escape and leave the more difficult questions for later. It is clear however, that the Taliban’s advance and the West’s miscalculations, were down to the Taliban’s ability to coerce the Afghan population and military to acceptance without having to resort to full blown conflict. In this David and Goliath story, the killing blow was not caused by a slingshot and pebble but by storytelling and narrative.

Coercion in conflict is not new, it is as ancient as war itself but now, more than ever, the ability to coerce is seen as a weapon system and a mechanism to win conflicts below the threshold. Coercion can take many forms, positive or negative. Populations or communities can be exposed to fear, money, promises of a better life, claims of cultural or religious allegiance, identification of a common enemy or linking through national ties. The type and the effectiveness of coercion is dependent on the target audience, some will succumb to fear, some will galvanise behind a hatred of a common enemy or rally to a flag. What is important to a coercive offensive is the mechanism of the transmission of the message. The narrative war is all important in contemporary conflict. The Taliban messaging in Afghanistan was powerful enough to create regime change without full blown conflict: a coup d’état which although not truly bloodless, the violence was unattributable to those that control the narrative.

The speed and capability of the Taliban in controlling the narrative to achieve military effect is, on one hand, an incredible feat of using the correct message to strike accord with the population (be that positive or negative motivations), and on the other, an incredible defeat by western governments not to understand the mood of the population beyond the boundaries of the cities.

Will History Teach us Nothing?

This refusal to accept the truth is not a new phenomenon. In 1990, Soviet troops were gone from Afghanistan but the country was gripped by civil war with the US-backed mujahideen fighting the Soviet-backed government of President Najibullah.

Faced with an insurgency armed with modern Stinger missiles, Najibullah vastly underestimated the mujahideen’s propaganda campaign. Evocative imagery on posters disseminated by the mujahideen promoted Islam and a sacred duty to free the Afghan nation from Soviet influence. This and other misinformation swayed the ranks of Najibullah’s defence forces, lowering morale to such an extent that there were numerous reports of frontline desertions. Today the Taliban make the same claim.

The Kakar History Foundation recently released a series of letters between Najibullah and historian Hassan Kakar. These letters shed new light on both the attitude and the mindset of Najibullah and exiled intellectuals. They also show the importance of the struggle to control the narrative: the ability to do so is seen as almost coequal to military victories.

Najibullah was notoriously insular, and one wonders whether his efforts might have achieved greater success had he had access to an improved and global communications infrastructure, and received feedback from beyond his network of trusted friends and advisors. Thirty years later, one also wonders if today’s Afghan government has learned those lessons and can leverage modern strategic communications tools better than Najibullah.

Gauging opinion

Reading the Najibullah-Kakar correspondence, it is clear that Najibullah did not capture the mood of his people.

‘Although the war and armed aggression continue, the national reconciliation policy has captured the hearts and thoughts of millions of Afghans. It has brought about a major weakening in the militant and non-conciliatory forces of the extremists,’ writes Najibullah with confidence, revealing an astounding illiteracy of sentiments and allegiances across the country. Kakar responds presciently, pointing out what he sees: ‘A total lack of [public] trust in Kabul government and a complete divorcement of the latter from the people.’

As the former head of KhAD (the Afghan State Intelligence Agency), Najibullah relied on feedback provided by his vast network of spies and informants rather than media reports and polling data. His feedback may have been worthwhile as intelligence on enemy forces and foes, but it did not provide an accurate sense of popular opinion. Nor did Najibullah encourage an open press or polls to balance these views. Without reliable feedback on the issues closest to his citizens, Najibullah was blind as to how to respond.

Repeating Mistakes

In 2008 a study was conducted of southern Afghanistan centred on Kandahar. The study was intended to gauge the opinion of the local population about the performance and acceptance of the coalition forces. The study took place over 2 months and involved interviewing key individuals, the general public and elements of the community such as shop keepers, teachers, farmers and so on. The questions were simple and all revolved around 2 central points:

· What do you want the coalition to provide?

· Do you trust the coalition to provide?

Once the data had been collected and analysed the resulting intelligence was transposed on to a heat map depicting support or trust in the coalition to deliver on promises; red was bad, green was good. Once the map had been colourised, it was resoundingly red. Even the city of Kandahar was red, which at the time, represented a strategic failure to maintain influence and security over the second most important city in Afghanistan.

The data was checked and re-checked as it represented a strategic failure and went against most of the coalition’s beliefs. Once the officer in charge was satisfied, the intelligence was presented to the general. Just like Najibullah, some 30 years before, the General refused to see the picture presented by the intelligence and preferred to rely on verbal reports from his friends. The truth displayed, as Kakar had reported previously, “A total lack of [public] trust in [the coalition]and a complete divorcement of the latter from the people[s’ wishes].” Where the coalition built schools, the locals wanted security, where the coalition invested in roads, the population wanted security… the story was clear.

The coalition had constructed a narrative around their bias and culture that seemed to target their domestic audience rather than the Afghan people. The narrative played to western concerns pushing stories that would strike resonance and perpetuate domestic public support, stories such as building schools and improving female rights. The coalition forgot to think about their true audience and continued to believe their own construct even when confronted by contrary intelligence.

Accepting realities and constructive feedback is fundamental to gauging public sentiments and calibrating the failure or success of policy. The First Vice President Amrullah Saleh’s recent denial that Afghan troops were surrendering without resistance indicates that the Afghan government is oblivious to the fact that it is losing ground in the narrative war. The Taliban out manoeuvred the Afghan government by efficiently communicating constructed realities and promoting their cause. The public, the government and a majority of the Afghan defence forces were coerced by a powerful combination of ‘carrot and stick’ narratives that convinced them that not only was resistance futile, but resistance would also be contrary to the benefit of the country that they loved.

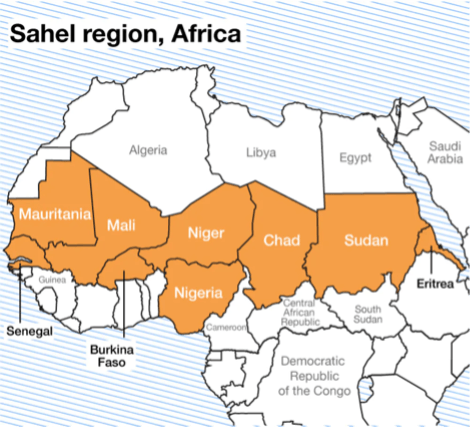

The Ripples on the Pond

While the media is focused on the unfolding events around Kabul airport, the ripples of the narrative used in Afghanistan lap the shores of the Sahel. Militants, insurgents, terrorist organisations will all be taking strength from the withdrawal of the coalition in the face of the Taliban. The fact that the Taliban will not negotiate an extension to the 31 August deadline in the face of a US led force, is a powerful message and will set the stall out for the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and other organisations bent on imposing their will on a population. Imagine the narrative being transmitted now, “Your American saviours will not come, even if they do, they will not stay… they will abandon you just as they have abandoned those in Afghanistan.” It does not matter if the facts of this message are not true or not, want matters is that the message resonates with the audience and creates coercive effect.

In March 2021 Brig. Gen. Les Kodlick, Air Force public affairs director, spoke at the AFA’s Air Warfare Symposium in Orlando, Fla. He spoke about the Taliban’s attempt to build a narrative. However, he (possibly) wrongly identified that the counter narrative from the US should reflect the number of deaths caused by the Taliban. Kodlick noted that “last year nearly 80% of Afghan casualties were caused by the Taliban.” This fact, he suggested, the United States cannot tell often enough, by releasing photographs and video imagery showing the truth.

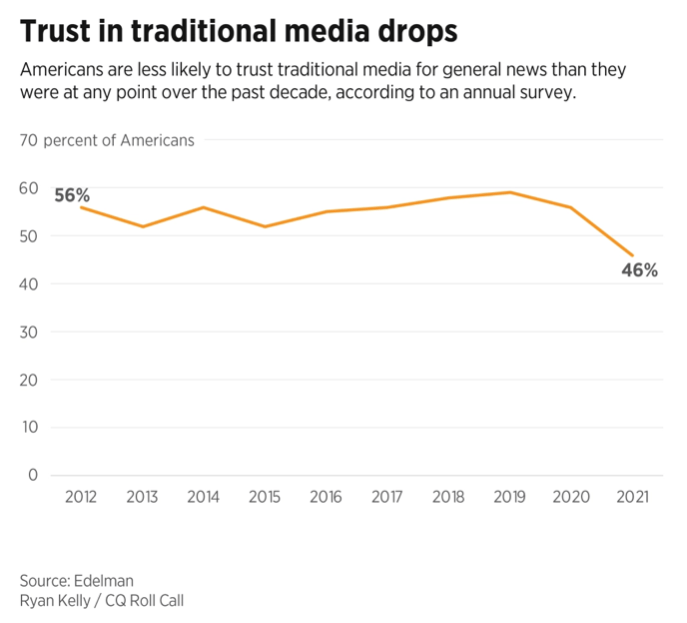

Here is an important lesson to learn. Truth, sometimes, does not matter. Trust in social media and media is on the decline[1].

[1] Source: Edelman Ryan Kelly / CQ Roll Call

Therefore, stories carried by the media will often be viewed with scepticism. This is exacerbated when the author of the article is from a country that is knowingly pushing a bias. The narrative is more effective it it relates to the audience: if it shares fears and loves, if it links to culture and other significant touch points. The facts may be modified to make the story line more compelling. The good become God like and the enemy become demonic. Good story tellers such as those famed from the Silk Road or more recently in Disney and Hollywood adhere to this method of story telling. In the words of the UK’s joint Concept Note 2/18 Information Advantage, “Experts are out, opinion is in; it matters not how verifiable the assertion, it only matters that it attracts attention – true believers, sceptics, conspiracy theorists and artificial intelligence can do the rest”

The coalition narrative in Afghanistan centred too much on statistics and too little on the heuristics. By indicating that the Taliban are responsible for 80% of the deaths is an admittance that the coalition are powerless to prevent Taliban aggression. In a culture that respects power, who is the winner here?

The Centrality of Influence

In 2018, 360iSR published their first paper on the centrality of influence in contemporary conflict, since then we have been working with organisations to help define and map the cognitive space and to accept that narrative warfare for cognitive effect is the weapon of choice for the modern sub threshold actor. The recent events in Afghanistan reflect this opinion and suggest that the impact of these events will stretch far beyond the lines in the sand created all those years ago.

We cannot afford to make the mistakes of those that have gone before us. We cannot be like Najibullah and live in ivory towers surrounded by a room of mirrors. We cannot avoid the ugly truth of intelligence that maps a counter position to our own, no matter how dear we hold that opinion or how closely we hold it to our ideals. If we are to continue to be a force for good in the world, we need to evolve, to become more understanding of the cognitive domain and the effects that are created therein. Without this capability we will become irrelevant to many conflicts in the world. We may be able to project power in the form an aircraft carrier and F35s, which is important in the peer-to-peer struggle, but can we understand and defeat a greater, more real threat that is knocking on the door of the Sahel?

360iSR is now working in these countries on the request of trusted governments to help develop intelligence beyond the limited scope of Multi Domain Operations. We encourage an ISR and Intelligence capability that encompasses the physical and information domains and, importantly, the cognitive domains. We are creating Intelligence fusion centres that will aid local governments and militaries to make informed decisions across all 3 domains and enable counter narrative operations. As the fallout from the events in Afghanistan ripple across the Sahel area, 360iSR will be working hard to ensure that trusted governments in the region, are armed with information advantage across the total mission space to counter the narrative and defeat the opponent.

Summary

In the story “The Arabian Nights”, the great king Shahryar was betrayed by his wife. This experience led him to hate all women and exact retribution by marrying a new wife every evening only to have her strangled by morning. Outraged by this, the King’s Grand Vizir’s eldest daughter, Scheherazade, said, “Father, I have a favour to ask you. Will you grant it to me?”. The Grand Vizir could not refuse. “I am determined to stop this barbaric practice and to deliver the girls and mothers from this awful fate that hangs over them”. Scheherazade continued. “I implore you, with all of my heart to allow the honour of marrying the King to fall to me.” Knowing that this would mean certain death the Grand Vizir refused. However, through argument and persuasion, Scheherazade got her way and was married that evening.

The King was not interested in Scheherazade and made his usual plans to have her killed. That is until Scheherazade started telling stories. Each story compelling and leading to the next. Each night the King spared her life as he wanted to know how the stories ended. The narrative continued for 101 nights after which the King had changed his mind about Scheherazade and women in general. The story ends with the King repenting his error and marrying Scheherazade.

The power of the narrative is ageless. In the metaphorical 1001 nights of the Taliban in Afghanistan, compelling stories were told conjuring images of an evil enemy, powerless outside of the cities; of a National government corrupt and un-Islamic; of how the enemy of the Taliban are always defeated and of a shared culture, ancestry and history. These stories coerced the population to believe them. The coercion may have been through fear, or it may be through a carefully constructed narrative that linked cultures, identified commonality, and promised improvements. However, it was achieved under the watchful eyes of the coalition and governments: insidious, barely detectable, yet catastrophically powerful.

The cognitive domain is the mission space of the contemporary contest. We must learn this lesson and take measures now to ensure cognitive defence, and, if need be, cognitive offense. Without these capabilities we will look at the Sahel as shadow governance once again takes hold, as narratives take root and, ultimately, as battles are won before there is a chance to fight.